Martial Arts Training and Mental Health an Exercise in Selfhel

- Study protocol

- Open Access

- Published:

The effects of martial arts participation on mental and psychosocial health outcomes: a randomised controlled trial of a secondary school-based mental health promotion plan

BMC Psychology volume 7, Commodity number:lx (2019) Cite this article

Abstract

Background

Mental wellness problems are a significant social result that have multiple consequences, including broad social and economical impacts. Even so, many individuals do non seek assistance for mental health problems. Limited inquiry suggests martial arts grooming may be an efficacious sports-based mental wellness intervention that potentially provides an inexpensive culling to psychological therapy. Unfortunately, the small number of relevant studies and other methodological issues pb to uncertainty regarding the validity and reliability of existing research. This study aims to examine the efficacy of a martial arts based therapeutic intervention to improve mental health outcomes.

Methods/design

The report is a 10-week secondary school-based intervention and will be evaluated using a randomised controlled trial. Data will be collected at baseline, post-intervention, and 12-week follow-up. Power calculations indicate a maximum sample size of n = 293 is required. The target age range of participants is 11–14 years, who volition be recruited from government and cosmic secondary schools in New Southward Wales, Australia. The intervention will be delivered in a face-to-face grouping format onsite at participating schools and consists of 10 × 50–60 min sessions, once per week for 10 weeks. Quantitative outcomes will exist measured using standardised psychometric instruments.

Discussion

The electric current study utilises a robust design and rigorous evaluation procedure to explore the intervention's potential efficacy. Equally previous research examining the training effects of martial arts participation on mental health outcomes has not exhibited comparable scale or rigour, the findings of the study volition provide valuable evidence regarding the efficacy of martial arts training to improve mental health outcomes.

Trial registration

Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Register ACTRN12618001405202. Registered 21st Baronial 2018.

Background

Mental wellness problems are a significant social issue that have multiple consequences; ranging from personal distress, disability, and reduced labour force participation; to wider social and economical impacts. The annual global price of mental health bug was estimated equally $USD two.5 trillion by the World Health Organisation [1]; and the annual cost of mental affliction in Australia has been estimated as $AUD 60 billion [2]. These costs are projected to increment 240% past 2030 [1].

Notwithstanding, for a variety of reasons including stigmatisation of mental wellness and the cost and poor availability of mental health treatment, many individuals do not seek help for mental health problems [3]. Consequently, information technology is of import to consider the application of culling and costless therapies regarding mental health handling. Martial arts preparation may be a suitable alternative, equally information technology incorporates unique characteristics including an emphasis on respect, self-regulation and health promotion. Due to this, martial arts grooming could be viewed equally a sports-based mental health intervention that potentially provides an inexpensive culling to psychological therapy [4]. However, the efficacy of this approach has received piffling research attention [5].

Existing martial arts inquiry has mostly focused on the physical aspects of martial arts, including physical health benefits and injuries resulting from martial arts exercise [6], while few studies accept examined whether martial arts preparation addressed mental health problems or promoted mental health and wellbeing. Several studies report that martial arts preparation had a positive result reducing symptoms associated with feet and depression. For example: (a) preparation in tai-chi reduced anxiety and depression compared to a non-handling condition [vii], (b) karate students were less decumbent to low compared to reported norms for male college students [eight], and (c) a study examining a six-month taekwondo program reported significantly reduced feet [9]. Similarly, several studies written report martial arts grooming promotes characteristics associated with wellbeing including: (a) a group of female participants reported higher self-concept compared to a comparison grouping after studying taekwondo for 8 weeks [10], and (b) a six-month taekwondo programme found increased self-esteem following the intervention [9].

A contempo meta-analysis examining the effects of martial arts training on mental health examined 14 studies and establish that martial arts training had a positive outcome on mental health outcomes (Moore, B., Dudley, D. & Woodcock, S. The effect of martial arts preparation on mental health outcomes: a systematic review and metaanalysis, Nether review). The written report found that martial arts training had a medium effect size regarding reducing internalising mental health problems, such as anxiety and depression; and a small effect size regarding increasing wellbeing.

However, despite mostly positive findings the research base examining the psychological effects of the martial arts training exhibits significant methodological problems [11, 12]. These include definitional and conceptual problems, a reliance on cantankerous-sectional enquiry designs, small sample sizes, self-choice effects, the employ of self-written report measures without third party corroboration, absence of follow-up measures, non accounting for demographic differences such equally gender, and issues controlling for the role of the instructor. These bug may limit the generalisability of findings and advise uncertainty regarding the validity and reliability of previous research.

This report seeks to examine the human relationship between martial arts training and mental health outcomes, while addressing the methodological limitations of previous studies. The intervention examined by the study is a bespoke plan based primarily on the martial art taekwondo and incorporating psycho-education developed for the intervention. Importantly, this written report aims to examine the efficacy of a martial arts based therapeutic intervention to improve mental health outcomes.

Methods/design

Study design

This report is a 10-week secondary school-based intervention and will exist evaluated using a randomised controlled trial. Ethics approval has been sought and obtained from an Australian University Human Research Ideals Commission, the New South Wales (NSW) Department of Pedagogy, and the Cosmic Education Diocese of Parramatta. The study is registered with the Australian and New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ACTRN12618001405202). The study protocol was also reviewed externally past school psychologists employed by the NSW Department of Education.

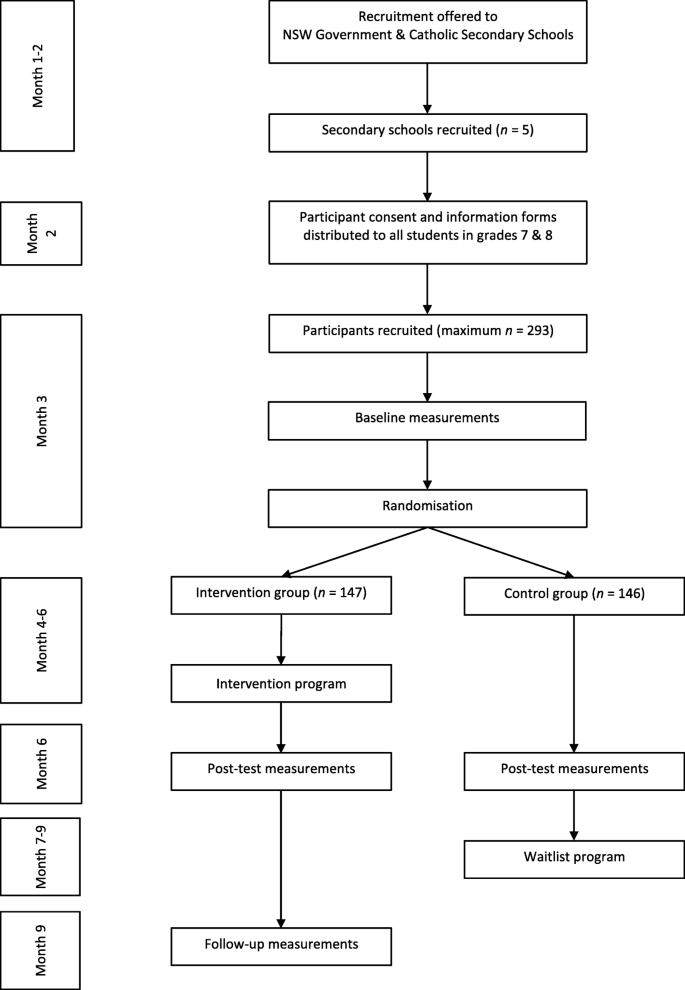

Researchers volition conduct baseline assessments at participating schools subsequently the initial recruitment processes. Following baseline assessments and randomisation, the intervention group will receive the intervention after which postal service-intervention assessment will be conducted. A 12-week post-intervention (follow-up) assessment will as well exist conducted. The control grouping will receive the aforementioned intervention program after the first post-intervention cess and will not be measured at follow-upward. The pattern, conduct and reporting of this study will adhere to the Consolidation Standards of Reporting Trials (Espoused) guidelines for a randomised controlled trial [xiii]. Participants and caregivers volition provide written informed consent.

Sample size calculation

Power calculations were conducted to determine the sample size required to observe changes in mental health related outcomes resulting from martial arts training. Statistical ability calculations assumed baseline-post-examination expected event size gains of d = 0.iii, and were based on ninety% power with alpha levels set at p < 0.05. The minimum completion sample size was calculated as northward = 234 (intervention group: n = 117, control group: n = 117). Equally participant drop-out rates of 20% are common in randomised controlled trials [fourteen], the maximum proposed sample size was n = 293 (intervention group: northward = 147, command group: north = 146).

Recruitment and study participants

To be eligible to participate in the study, schools must be government or catholic secondary schools in NSW, Australia. All eligible schools (north = 140) will exist sent an initial electronic mail with an invitation to participate in the study. Schools that respond to the initial email volition be pooled and receive a follow up call in random club from the project researchers to discuss whether they would similar to participate in the study. The kickoff five schools that demonstrate interest will so be recruited into the study.

Inclusion criteria for participation in the study includes: (a) participants are currently enrolled in grades vii or 8, and (b) participants are within an age range 11–14 years. Exclusion criteria: concurrent martial arts grooming volition exclude participation in the study, even so prior experience of martial arts training is non an exclusion criteria. All students at participating schools who meet these criteria volition be invited to participate in the study. Participant and caregiver information and consent forms will be provided to students. Two follow-upwards letters will be sent later at two week intervals. Students who respond to the invitation volition be pooled and randomly allocated into the study, or not included in the study.

Randomisation into intervention and command grouping will occur after baseline assessments. A uncomplicated computer algorithm will be used to randomly classify participants into intervention or control groups. This volition exist performed by a researcher not directly involved in the study. Figure 1 provides a flowchart of the timeline for the written report.

Flowchart of report

Intervention design

Intervention clarification

The intervention volition exist delivered in a confront to face group format onsite at participating schools. The intervention will be 10 × fifty–60 min sessions, in one case per week for x weeks. Each intervention session will include:

- (a)

Psycho-educational activity – guided group based discussion. Topics include respect, goal-setting, self-concept and cocky-esteem, courage, resilience, bullying and peer force per unit area, self-intendance and caring for others, values, and, optimism and hope;

- (b)

Warm up – including jogging, star jumps, push ups, and sit ups;

- (c)

Stretching – including hamstring stretch, triceps stretch, figure four stretch, butterfly stretch, lunging hip flexor stretch, articulatio genus to chest stretch, and standing quad stretch; and,

- (d)

Technical do – including stances, blocks, punching, and kicking.

Additionally, intervention sessions intermittently include (alternated throughout the program):

- (eastward)

Patterns practice – a design is a choreographed sequence of movements consisting of combinations of blocks, kicks, and punches performed as though defending against one or more imaginary opponents;

- (f)

Sparring – based on tai-chi sticking hands exercise (which has been included as an alternative to traditional martial arts sparring); and

- (g)

Meditation – based on breath focusing practice.

In the final session the intervention will conclude with a formal martial arts grading where participants will be awarded a yellow belt subject field to demonstration of martial arts techniques (stances, blocks, punching, and kicking) and the design learnt during the program. While it is desirable for participants to nourish all x sessions to achieve intervention dose, information technology is unrealistic to assume all sessions will be attended. Research has suggested that determining an adequate intervention dose in wellness promotion programmes can be based on level of participation and whether participants did well [15]. In the electric current study intervention dose will be assumed if participants successfully complete the formal grading and are awarded a yellow belt. It is important to note that aggressive physical contact is not part of the intervention program. The intervention volition exist delivered past a (1) registered psychologist with minimum 6 years' experience, and (2) 2nd Dan/level black-belt taekwondo instructor with minimum 5 years' experience. Materials used during the intervention will include martial arts belts (white and yellow), and martial arts grooming equipment (for case strike paddles, strike shields).

Theoretical framework

The intervention evolution and implementation will exist based on a traditional martial arts model, dichotomous wellness model, and social cognitive theory. Inquiry examining the relationship between the martial arts and mental wellness has typically used a bipartite model [xvi] which distinguishes between traditional and modern martial arts. The intervention is based on a traditional martial arts perspective, which emphasizes the non-ambitious aspects of martial arts including psychological and philosophical evolution [17].

The absence of an explicit health model is a significant methodological limitation of previous research examining the mental health outcomes of martial arts training. The dominant models of mental health are based on the homeostatic supposition that normal health reflects the trend towards a relatively stable equilibrium; and that the dysregulation of homeostatic processes causes ill-health [eighteen]. These models can be defined dichotomously as having a: (1) pathological basis (deficit model) which refers to the presence or absence of disease based symptoms such as depression or anxiety; and (2) wellbeing basis (strengths model) which refers to the presence or absenteeism of beneficial mental health characteristics such every bit resilience or self-efficacy. While considering both aspects of the mental health continuum, this written report was particularly interested in the strengths model and examined the wellbeing characteristics of resilience and self-efficacy.

Social cognitive theory suggests that knowledge tin can be acquired through the observation of others in the context of social interactions, experiences, and media influences; and explains homo behaviour in terms of continuous reciprocal interaction between personal cerebral, behavioural, and environmental influences [19]. The theory is useful for explaining the learning processes in the martial arts, which include: (a) modelling – where learning occurs through the observation of models; (b) result expectancies – to learn a modelled behaviour the potential outcome of that behaviour must exist understood (for example, the apprehension of rewards or punishment); and (c) self-efficacy – the extent to which an private believes that they tin can perform a behaviour required to produce a item issue [19].

The report'south theoretical framework incorporating a traditional martial arts model, dichotomous wellness model and social cognitive theory facilitates examination of the effects of martial arts training on mental health, ranging from mental health issues to factors associated with wellbeing such as resilience and self-efficacy. Further, the framework may decide the efficacy of martial arts training as an alternative mental health intervention that improves mental health outcomes.

Outcomes

Evaluation of the intervention program will involve a variety of standardised psychometric instruments to report on mental health related outcomes. Instruments include the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) [twenty], Kid and Youth Resilience Measure (CYRM) [21], and Cocky-Efficacy Questionnaire for Children (SEQ-C) [22]. All upshot fourth dimension-points volition be examined 1 calendar week pre-intervention, ane week post-intervention, and 12-calendar week post-intervention (follow-up).

Behavioural and emotional difficulties

The primary effect measured by the SDQ will be mean total difficulties. Additionally, the SDQ will measure the post-obit secondary outcomes: emotional difficulties, comport difficulties, hyperactivity difficulties, peer difficulties, and pro-social behaviour.

Full difficulties was selected equally a primary outcome equally it provides an overview of participants' psychological problems. The SDQ scale is a commonly used psychometric screening tool recommended for use by the Australian Psychological Society [23] and has been normed for the Australian population.

Resilience

The principal event measured by the CYRM will be mean total resilience. Additionally, the CYRM volition measure the following secondary outcomes: private capacities and resources, relationships with primary caregivers, and contextual factors.

Resilience was selected as a primary outcome as information technology is a current focus of research regarding psychological strengths, merely has not been examined regarding the outcome of martial arts training. The CYRM-28 was used in the study as it efficiently operationalises the theoretical aspects of resilience in a valid and reliable way, but is shorter than comparable scales (for example the Resilience Scale for Children and Adolescents [24]).

Cocky-efficacy

The principal result measured by the SEQ-C will be hateful total cocky-efficacy. Additionally, the SEQ-C volition measure the following secondary outcomes: bookish self-efficacy, social self-efficacy, and emotional self-efficacy.

Self-efficacy was selected as a primary consequence as this operationalised a relevant component of social cognitive theory, which is important regarding the hypothesised learning processes in the intervention. The SEQ-C was used in the written report as information technology operationalises cocky-efficacy for adolescents in an educationally relevant context.

Statistical methods

Statistical analysis of the primary and secondary outcomes will be conducted using SPSS statistics version 25 (IBM SPSS Statistics, 2017) and blastoff levels will exist fix at p < 0.05.

The nerveless psychometric test data volition be consolidated into subscale variables using factor analysis and the internal consistency of each variable will exist examined to decide reliability. Items to be included in the scale variables volition be added and computed to create composite scores. Repeated measures univariate analysis of variance (ANOVA), and multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) will primarily be used to analyse test data. Ordinal regression volition be used to analyse test data based on psychometric measures using a three-point Likert scale. Interpretation of effect sizes will reflect Cohen's suggested small, medium, and large outcome sizes, where partial eta squared sizes are equal to 0.10, 0.25, and 0.40 respectively [25].

Age, school grade level, sex activity, socio-economical status and cultural background volition be included as covariates in the assay.

Give-and-take

The primary aim of this written report is to evaluate the training furnishings of martial arts participation on mental wellness outcomes. The report volition use a randomised controlled trial of secondary school aged participants.

Previous studies examining the impact of martial arts training on mental health and wellbeing have found positive results, which has likewise been confirmed past a systematic review and meta-assay. Results take included martial arts grooming reducing symptoms associated with feet and depression; and promoting characteristics associated with wellbeing. However, the modest number of relevant studies and noted methodological problems atomic number 82 to uncertainty regarding the validity and reliability of existing inquiry.

The current study utilises a robust design with baseline, post-test and follow-up measures to examine the views of participants and includes a rigorous evaluation process using quantitative information to explore the program's potential efficacy. This is a clear strength of this study and is important due to the study's multi-site delivery. The current study has not used a qualitative arroyo which is a limitation of the research. Qualitative work is planned for future inquiry to explore issues such as machinery of impact.

Conclusion

The findings of this study volition provide valuable evidence regarding the training effects of martial arts participation on mental health outcomes, and data for inquiry groups looking for alternative or complementary psychological interventions. To our cognition, no previous studies have reported the training effects of martial arts participation on mental health outcomes on a scale comparable to the current study while maintaining a similarly robust blueprint and rigorous evaluation procedure. This study has the potential to change public health policy, and schoolhouse-based policy and do regarding management of mental health outcomes and raise a range of wellness promoting behaviours in schools.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the electric current study will be available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- $AUD:

-

Australian dollar

- $USD:

-

The states dollar

- ACTRN:

-

Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry Number

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of variance

- Consort:

-

Consolidation standards of reporting trials

- CYRM:

-

Kid and youth resilience measure

- MANOVA:

-

Multivariate analysis of variance

- NSW:

-

New South Wales

- SDQ:

-

Strengths and difficulties questionnaire

- SEQ-C:

-

Cocky-efficacy questionnaire for children

- SPSS:

-

Statistical packages for the social sciences

References

-

World Wellness System. Out of the shadows: making mental health a global developmental priority. (2016). http://www.who.int/mental_health/advocacy/wb_background_paper.pdf Accessed 20 Jan 2018

-

Australian Regime National Mental Health Commission. Economics of Mental Health in Commonwealth of australia (2016). http://www.mentalhealthcommission.gov.au/media-heart/news/economics-of-mental-wellness-in-australia.aspx Accessed 20 June 2018.

-

Corrigan P. How stigma interferes with mental health care. Am Psychol. 2004;59(vii):614–25.

-

Fuller J. Martial arts and psychological health. Brit J Med Psychol. 1988;61:317–28.

-

Macarie I, Roberts R. Martial arts and mental health. Contemp Psychothera. 2010;two:i), 1–4.

-

Burke D, Al-Adawi S, Lee Y, Audette J. Martial arts every bit sport and therapy and grooming in the martial arts. J Sport Med Phys Fit. 2007;47:96–102.

-

Li F, Fisher K, Harmer P, Irbe D, Tearse R, Weimer C. Tai chi and self-rated quality of slumber and daytime sleepiness in older adults: a randomised controlled trial. J Am Ger Soc. 2004;52:892–900.

-

McGowan R, Jordan C. Mood states and concrete activity. Louis All Wellness Phys Ed Rec Dan J. 1988;fifteen(12–13):32.

-

Trulson M. Martial arts training: a "novel" cure for juvenile delinquency. Hum Relat. 1986;39(12):1131–xl.

-

Finkenberg M. Effect of participation in taekwondo on higher women's self-concept. Percept Motor Skills. 1990;71:891–4.

-

Tsang T, Kohn Yard, Chow C, Singh 1000. Wellness benefits of kung Fu: a systematic review. J Sport Sci. 2008;26(12):1249–67.

-

Vertonghen J, Theeboom 1000. The socio-psychological outcomes of martial arts do among youth: a review. J Sport Sci Med. 2010;ix:528–37.

-

Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz K, Montori V, Gotzsche P, Devereaux P, et al. Espoused 2010 caption and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ. 2010;340:698–702.

-

Wood A, White I, Thompson South. Are missing issue data adequately handled? A review of published randomized controlled trials in major medical journals. Clin Trials. 2004;1:368–76.

-

Legrand K, Bonsergent E, Latarche C, Empereur F, Collin J, Lecomte Due east, et al. Intervention dose estimation in wellness promotion programmes: a framework and a tool. Application to the diet and physical activity promotion PRALIMAP trial. BMC Med Res Meth. 2012;12:146.

-

Donohue J, Taylor K. The classification of the fighting arts. J Asian Mart Art. 1994;3(4):ten–37.

-

Twemlow S, Biggs B, Nelson T, Venberg East, Fonagy P, Twemlow S. Furnishings of participation in a martial arts based antibullying program in elementary schools. Psychol Schools. 2008;45(ten):1–fourteen.

-

Antonovsky A. Unravelling the mystery of health. San Francisco: Jossey Bass; 1987.

-

Bandura A. Social Learning Theory. New York: General Learning Press; 1977.

-

Goodman, R. Strengths and difficulties questionnaire; 2005. http://world wide web.sdqinfo.com.

-

Ungar, K., & Liebenberg, L., Assessing Resilience across Cultures Using Mixed-Methods: Structure of the Kid and Youth Resilience Mensurate-28. J Mixed-Meth Res. 2011; 5(2), 126–149.

-

Muris P. A brief questionnaire for measuring self-efficacy in youths. J Psych Behav Appraise. 2001;23(iii):145–9.

-

Australian Psychological Society. Clinical Assessment Resources. 2011 https://groups.psychology.org.au/Assets/Files/Final_clinical_assessment_guide_January_2011.pdf Accessed xvi Aug 2018.

-

Prince-Embury Southward. Resilience scales for children and adolescents: a profile of personal strengths. Minneapolis: Pearson; 2007.

-

Richardson J. Eta squared and fractional eta squared every bit measures of event size in educational research. Ed Res Rev. 2011;six(2):135–47.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Writer information

Affiliations

Contributions

BM conceived the research aims, conducted the literature search, primarily wrote the manuscript and had principal responsibility for the last content. DD and SW reviewed and approved the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ideals approving has been sought and obtained from an Australian University Homo Research Ethics Committee (Reference No: 5201700901), the NSW Department of Education (Reference No: DOC18/257488), and Cosmic Education Diocese of Parramatta (Reference No: 28032018).

Written consent to participate is required from participants and caregivers.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional data

Publisher'southward Notation

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted utilise, distribution, and reproduction in whatever medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original writer(south) and the source, provide a link to the Artistic Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Eatables Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/nil/one.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

About this commodity

Cite this article

Moore, B., Dudley, D. & Woodcock, South. The effects of martial arts participation on mental and psychosocial health outcomes: a randomised controlled trial of a secondary school-based mental health promotion program. BMC Psychol 7, threescore (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-019-0329-5

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-019-0329-5

Keywords

- Mental health

- Martial arts

- Resilience

- Self-efficacy

- Preventative medicine

- Alternative and complimentary therapies

Source: https://bmcpsychology.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40359-019-0329-5

0 Response to "Martial Arts Training and Mental Health an Exercise in Selfhel"

إرسال تعليق