to what order of animals does the sperm whale belong?

| Faux killer whale Temporal range: Middle Pleistocene–Recent[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

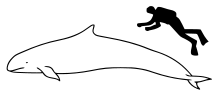

| Size compared to an boilerplate human | |

| Conservation status | |

| | |

| CITES Appendix II (CITES)[3] | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Club: | Artiodactyla |

| Infraorder: | Cetacea |

| Family: | Delphinidae |

| Genus: | Pseudorca |

| Species: | P. crassidens |

| Binomial proper noun | |

| Pseudorca crassidens (Owen, 1846) | |

| |

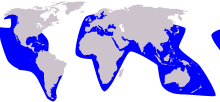

| Range of the false killer whale | |

| Synonyms[four] | |

| List of synonyms

| |

The false killer whale (Pseudorca crassidens) is a species of oceanic dolphin that is the simply extant representative of the genus Pseudorca. Information technology is constitute in oceans worldwide but mainly frequents tropical regions. It was beginning described in 1846 as a species of porpoise based on a skull, which was revised when the first carcasses were observed in 1861. The proper noun "false killer whale" comes from the similar skull characteristics to the orca (Orcinus orca), which has been known as the killer whale.

The simulated killer whale reaches a maximum length of vi g (20 ft), though size tin can vary effectually the world. Information technology is highly sociable, known to form pods of upwards to 50 members, and can also form pods with other dolphin species, such equally the common bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus). Further, it can form close bonds with other species, also as partake in sexual (including both heterosexual and homosexual) interactions with them. Conversely, the false killer whale has also been known to feed on other dolphins, though it typically eats squid and fish. It is a deep-diving dolphin, with a maximum recorded depth of 927.5 m (3,043 ft); its maximum speed is around 29 km/h (xviii mph).

Several aquariums around the world keep i or more false killers, although the species' assailment towards other dolphins makes it less desirable. Information technology is threatened by fishing operations, as it tin get entangled in fishing gear. It is drive hunted in some Japanese villages. The faux killer whale has a tendency to mass strand given its highly social nature, with the largest stranding consisting of 805 beached at Mar del Plata, Argentina. Well-nigh of what is known of this species comes from examining stranded individuals.

Taxonomy [edit]

Analogy of the skull

The false killer whale was first described by the British paleontologist and biologist Richard Owen in his 1846 book, A history of British fossil mammals and birds, based on a fossilised skull discovered in 1843. This specimen was unearthed from the Lincolnshire Fens nearly Stamford in England, a subfossil deposited in a marine surround that existed effectually 126,000 years ago.[1] [five] The skull was reported equally present in a number of museum collections, only noted every bit lost by William Henry Bloom in 1884.[vi] Owen compared the skull to those of the long-finned pilot whale (Globicephala melas), beluga whale (Delphinapterus leucas), and Risso'southward dolphin (Grampus griseus)–in fact, he gave it the nickname "thick toothed grampus" in light of this and assigned the beast to the genus Phocaena (a genus of porpoises) which Risso'due south dolphin was as well assigned to in 1846. The species name crassidens means "thick toothed".[5]

In 1846, zoologist John Edward Gray assigned the false killer whale to the genus Orca, which had been known as the killer whale (now Orcinus orca). Until 1861, when the first carcasses washed up on the shores of Kiel Bay in Denmark, the species was presumed to exist extinct. Based on these and a pod that beached itself three months afterwards in Nov, zoologist Johannes Theodor Reinhardt moved the species in 1862 to the newly erected genus Pseudorca, which established it as being neither a porpoise nor a killer whale.[7] [8] Still, the proper noun "false killer whale" comes from the apparent similarity between its skull and that of the killer whale.[9]

The simulated killer whale is a member of the family unit Delphinidae, the oceanic dolphins. It is part of the subfamily Globicephalinae, and its closest living relatives are Risso's dolphin, the melon-headed whale (Peponocephala electra), the pygmy killer whale (Feresa attenuata), the airplane pilot whales (Globicephala spp.), and possibly the snubfin dolphins (Orcaella spp.).[10] Ane subspecies was proposed by Paules Edward Pieris Deraniyagala in 1945, P. c. meridionalis, though there was not sufficient justification, and William Henry Blossom suggested in 1884 and later abandoned a distinction between northern and southern false killer whales; there are currently no recognized subspecies.[xi] Even so, individuals in populations effectually the globe tin take different skull structures and vary in average length, with Japanese false killer whales beingness 10–20% larger than South African false killer whales.[nine] [12] It tin can hybridize with the bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus) to produce fertile offspring called "wholphins".[9] [13]

Clarification [edit]

Pod of false killer whales

The faux killer whale is black or dark gray, though slightly lighter on the underside. It has a slender body with an elongated, tapered head and 44 teeth. The dorsal fin is sickle-shaped, and its flippers are narrow, short, and pointed, with a distinctive bulge on the leading edge of the flipper (the side closest to the head). The average body length is effectually 4.9 k (sixteen.1 ft), with females reaching a maximum size of 5 one thousand (sixteen.4 ft) in length and 1,200 kg (2,600 lb) in weight, and males 6 m (20 ft) long and 2,000 kg (4,400 lb) in weight. However, on boilerplate, males and females are about the aforementioned size. Newborns can be one.5–2.1 m (four.nine–vi.nine ft) in length.[9] [14] Body temperature ranges from 36–37.2 °C (96.8–99.0 °F), increasing during activity.[8] The teeth are conical, and there are 14–21 in the upper jaw and sixteen–24 in the lower.[15]

The false killer whale reaches physical maturity between 8 and 14 years, and maximum historic period in captivity is 57 years for males and 62 for females. Sexual maturity happens between 8 and xi years. In one population, calving occurred at vii twelvemonth intervals; calving can occur twelvemonth-circular, though it commonly occurs in tardily wintertime. Gestation takes around 15 months.[9] Females lactate for 9 months to 2 years.[16] The false killer whale is 1 of three toothed whales, the other two being the pilot whales, identified as having a sizable mail-reproductive lifespan after menopause, which occurs between ages 45 and 55.[17]

Being a toothed whale, the false killer whale can echolocate using its melon organ in the forehead to create audio, which it uses to navigate and find casualty.[18] The melon is larger in males than in females.[ix]

Behavior [edit]

The false killer whale has been known to interact non-aggressively with several dolphin species: the common bottlenose dolphin, the Pacific white-sided dolphin (Lagenorhynchus obliquidens), the crude-toothed dolphin (Steno bredanensis), the pilot whales, the melon-headed whale, the pantropical spotted dolphin (Stenella attenuata), the pygmy killer whale, and Risso'southward dolphin.[nineteen] [viii] [9]

The false killer whale may answer to distress calls and protect other species from predators, aid in childbirth by helping to remove the afterbirth, and has been known to interact sexually with bottlenose dolphins and pilot whales,[8] including homosexually.[20] It has been known to course mixed-species pods with those dolphins, probably due to shared feeding grounds. In Japan, these simply occur in winter, suggesting it is tied to seasonal food shortages.[9] [8] [xv]

A pod near Republic of chile had a 15 km/h (nine.3 mph) cruising speed, and imitation killer whales in captivity were recorded to have a maximum speed of 26.nine–28.8 km/h (sixteen.seven–17.ix mph), like to the bottlenose dolphin. Diving behavior is not well recorded, but one private near Japan dove for 12 minutes to a depth of 230 g (750 ft).[9] [21] In Nippon, ane individual had a documented dive of 600 m (2,000 ft), and one in Hawaii 927.5 m (3,043 ft), comparable to pilot whales and other similarly-sized dolphins. Its maximum dive time is likely xviii.v minutes.[15]

The false killer whale travels in large pods, evidenced by mass strandings, normally consisting of 10 to twenty members, though these smaller groups can exist function of larger groups; it is highly social and can travel in groups of more than 500 whales. These large groups may intermission up into smaller family groups of 4 to half dozen members while feeding. Members stay with the pod long-term, some recorded equally 15 years, and, indicated by mass strandings, share strong bonds with other members. It is thought it has a matrifocal family construction, with the mothers heading the pod instead of the father, like in sperm whales and pilot whales. Different populations around the world have different vocalizations, like to other dolphins. The false killer whale is probably polygynous, with males mating with multiple females.[ix] [fifteen] [22] [23]

Ecology [edit]

More often than not, the imitation killer whale targets a wide assortment of squid and fish of various sizes during daylight hours.[nine] [24] They typically target big species of fish, such as mahi-mahi and tuna.[25] In captivity, it eats 3.4 to 4.3% of its trunk weight per twenty-four hours.[fifteen] A video taken in 2016 near Sydney shows a grouping hunting a juvenile shark.[26] It sometimes discards the tail, gills, and stomach of captured fish, and pod members have been known to share food.[9]

In the Eastern Pacific, the false killer whale has been known to target smaller dolphins during tuna pocketbook-seine angling operations; at that place are cases of attacks on sperm whales (Physeter macrocephalus), and one instance confronting a dogie of a humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae). Killer whales are known to casualty on the false killer whale, and information technology also possibly faces a threat from big sharks, though there are no documented instances.[9] [8] [15] [27]

The false killer whale is a known host of several parasites: trematode Nasitrema in the sinuses, nematode Stenurus in the sinuses and lungs, an unidentified crassicaudine nematode in the sinuses, tum nematodes Anisakis simplex and Anisakis typica, acanthocephalan worm Bolbosoma capitatum in the intestines, whale lice Syncyamus pseudorcae and Isocyamus delphinii, and the whale barnacle Xenobalanus globicipitis. Some strandings had whales with large Bolbosoma infestations, such equally the 1976 and 1986 strandings in Florida.[8]

Population and distribution [edit]

The imitation killer whale appears to have a widespread presence in tropical and semitropical oceanic waters. The species has been constitute in temperate waters, merely these occurrences were possibly devious individuals, or associated with warm h2o events. It by and large does not go beyond fifty°N and below 50°Southward.[14] [19] It usually inhabits open up oceans and deep-h2o areas, though it may frequent coastal areas near oceanic islands.[28]

The faux killer whale is idea to be common around the world, though no total interpretation has been made.[29] The population in the Eastern Pacific is probably in the depression tens-of-thousands,[30] and around 16,000 near China and Nippon.[31] The population effectually Hawaii has been declining.[28]

Human interaction [edit]

The false killer whale is known to be much more than adaptable in captivity than other dolphin species, beingness hands trained and highly sociable with other species, and as such it is/was kept in several public aquariums around the globe, such equally in Nihon, the United States, the Netherlands, Hong Kong, and Commonwealth of australia. Individuals were mainly captured off California and Hawaii, and then in Nippon and Taiwan after 1980.[9] [eight] [fifteen] [xx] It has too been successfully bred in captivity.[nine] However, Chester, an orphaned newborn who was stranded in Tofino on Vancouver Island in 2014 and rescued by Vancouver Aquarium, died from a bacterial erysipelas infection in 2017 at the age of 3 and a half. Being the 5th whale to dice in the aquarium, Chester's death caused the Vancouver Park Board to ban the aquarium from acquiring more whales.[32] [33]

The false killer whale has been known to arroyo and offer fish it has caught to humans diving or boating. However, information technology also takes fish off of hooks, which sometimes leads to entanglement or swallowing the claw. Entanglement can cause drowning, loss of circulation to an bagginess, or impede the animate being's power to hunt, and swallowing the claw tin can puncture the digestive tract or can become a blockage. In Hawaii, this is probable leading to the pass up in local populations, reducing them past 75% from 1989 to 2009. The false killer whale is more than susceptible to organochloride buildup than other dolphins, being college up on the food chain, and stranded individuals around the world evidence higher levels than other dolphins. Information technology has been known to ride the wakes of large boats, which could put it at take chances of hit the boat propeller.[28] [15]

In a few Japanese villages, the false killer whale is killed in drive hunts using sound to herd individuals together and cause a mass stranding or corral them into nets before beingness killed.[34]

Beachings [edit]

Mar del Plata in Argentina in 1946, the largest false killer whale stranding

The faux killer whale regularly beaches itself, for reasons largely unknown, on coasts around the world, with the largest stranding consisting of 835 individuals on nine October 1946 at Mar del Plata in Argentina.[ix] [28] Unlike other dolphins, but similar to other globicephalines, the false killer whale usually mass strands in pods, leading to such high mortality rates. These can likewise occur in temperate waters outside its normal range, such as with the mass strandings in U.k. in 1927, 1935, and 1936.[23]

The 30 July 1986 mass stranding of 114 simulated killer whales in Flinders Bay, Western Australia was widely watched equally volunteers and the newly created Department of Conservation and Land Direction (At-home) saved 96 individuals, and founded an informal network for whale strandings.[35] [36] The ii June 2005 Geographe Bay stranding of 120 individuals in Western Australia, the fourth in the bay, was caused by a storm preventing the animals from seeing the shoreline; this as well caused a rescue effort of one,500 volunteers past Calm.[37] [38]

Since 2005, there take been seven mass strandings of simulated killer whales in New Zealand involving more ane individual, the largest on viii April 1943 on the Māhia Peninsula with 300 stranded, and 31 March 1978 in Manukau Harbour with 253 stranded.[fifteen]

Whale strandings are rare in southern Africa, merely mass strandings in this area are typically associated with the faux killer whale, with mass strandings averaging at 58 individuals. Hot-spots for mass strandings be along the declension of the Western Cape in South Africa; the almost recent in xxx May 2009 near the village of Kommetjie with 55 individuals.[39]

On 14 January 2017, a pod of around 100 beached themselves in Everglades National Park in Florida, and the remoteness of the area was detrimental to rescue efforts, causing the deaths of 81 whales. The other ii strandings in Florida were in 1986 with three beached whales from a pod of 40 in Cedar Key, and 1980 with 28 stranded in Key W.[40]

Conservation [edit]

The false killer whale is covered by the Agreement on the Conservation of Small Cetaceans of the Baltic, North East Atlantic, Irish and North Seas (ASCOBANS), and the Agreement on the Conservation of Cetaceans in the Blackness Bounding main, Mediterranean Sea and Face-to-face Atlantic Area (ACCOBAMS). The species is further included in the Memorandum of Understanding Concerning the Conservation of the Manatee and Small Cetaceans of Western Africa and Macaronesia (Western African Aquatic Mammals MoU) and the Memorandum of Understanding for the Conservation of Cetaceans and Their Habitats in the Pacific Islands Region (Pacific Cetaceans MoU).[41]

No accurate global estimates for the fake killer whale exist, so the species is listed as Near Threatened by the IUCN Redlist.[two] In November 2012, the United States' National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration recognized the Hawaiian population of false killer whales, comprising around 150 individuals, as endangered.[42]

See also [edit]

- Listing of cetaceans

References [edit]

- ^ a b Pseudorca crassidens at fossilworks.org (retrieved xi Baronial 2018)

- ^ a b Baird, R.W. (2018). "Pseudorca crassidens". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018: due east.T18596A145357488. doi:ten.2305/IUCN.U.k..2018-two.RLTS.T18596A145357488.en . Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- ^ "Appendices | CITES". cites.org . Retrieved xiv Jan 2022.

- ^ Perrin WF (ed.). "Pseudorca crassidens" . World Cetacea Database. Earth Register of Marine Species. Retrieved 4 August 2018.

- ^ a b Owen, R. (1846). A history of British fossil mammals and birds. J. Van Voorst. pp. 516–520.

- ^ Hershkovitz, P. 1966. Catalog of living whales. Bulletin of the United States National Museum 246: viii 1–259 [81]

- ^ Reinhardt, J. (1866). "Pseudorca crassidens". In Eschricht, D. F.; Lilljeborg, W.; Reindhardt, J. (eds.). Recent memoirs on the Cetacea. pp. 190–218.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Odell, D. K.; McClune, K. Thou. (1981). "Imitation killer whale Pseudorca crassidens (Owen, 1946)". In Ridgeway, S. H.; Harrison, R.; Harrison, R. J. (eds.). Handbook of marine mammals: the second book of dolphins and the porpoises. Elsevier. ISBN978-0-12-588506-v.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k 50 m n o p Baird, R. Due west. (2009). "Simulated Killer Whale: Pseudorca crassidens". In Perrin, W. F.; Würsig, B.; Thewissen, J. G. M. (eds.). Encyclopedia of marine mammals. Academic Printing. pp. 405–406. ISBN978-0-08-091993-5.

- ^ Cunha, H. A.; Moraes, L. C.; Medeiros, B. V.; Lailson-Brito, Jr, J.; da Silva, V. M. F.; Solé-Cava, A. M.; Schrago, C. G. (2011). "Phylogenetic Status and Timescale for the Diversification of Steno and Sotalia Dolphins". PLOS ONE. 6 (12): e28297. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...628297C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0028297. PMC3233566. PMID 22163290.

- ^ Stacey, P. J.; Leatherwood, Southward.; Baird, R. W. (1994). "Pseudorca crassidens" (PDF). Mammalian Species (456): one–six. doi:10.2307/3504208. JSTOR 3504208.

- ^ Ferreira, I. M.; Kasuya, T.; Marsh, H.; Best, P. B. (2013). "Simulated killer whales (Pseudorca crassidens) from Nippon and South Africa: Differences in growth and reproduction". Marine Mammal Science. 30 (1): 64–84. doi:10.1111/mms.12021. hdl:2263/50452.

- ^ Carroll, S. B. (13 September 2010). "Hybrids may thrive where parents fright to tread". New York Times.

- ^ a b "Imitation killer whale (Pseudorca crassidens)". Marine Species Identification Portal. Retrieved 26 January 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Zaeschmar, J. R. (2014). "Faux killer whales (Pseudorca crassidens) in New Zealand waters". Massey University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 August 2018. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- ^ Riccialdelli, L.; Goodall, R. Northward. P. (2015). "Intra-specific trophic variation in false killer whales (Pseudorca crassidens) from the southwestern Southward Atlantic Body of water through stable isotopes analysis". Mammalian Biology. 80 (4): 298–302. doi:10.1016/j.mambio.2015.01.003.

- ^ Photopoulou, T.; Ferreira, I. Grand.; All-time, P. B.; Kasuya, T.; Marsh, H. (2017). "Prove for a postreproductive phase in female fake killer whales Pseudorca crassidens". Frontiers in Zoology. 14 (30): 30. arXiv:1606.04519. doi:x.1186/s12983-017-0208-y. PMC5479012. PMID 28649267.

- ^ Au, W. W. L.; Pawloski, J. Fifty.; Nachtigall, P. E. (1995). "Echolocation signals and transmission beam design of a false killer whale (Pseudorca crassidens)". Periodical of the Acoustical Society of America. 98 (51): 51–59. Bibcode:1995ASAJ...98...51A. doi:10.1121/1.413643. PMID 7608405.

- ^ a b c Halpin, Luke R.; Towers, Jared R.; Ford, John Grand. B. (20 April 2018). "First tape of common bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus) in Canadian Pacific waters". Marine Biodiversity Records. 11: 3. doi:ten.1186/s41200-018-0138-1.

- ^ a b Chocolate-brown, D. H.; Caldwell, D. H.; Caldwell, Grand. B. (1966). "Observations on the wild and captive false killer whales, with notes on associated behavior of other genera of captive delphinids" (PDF). Los Angeles Canton Museum (95). Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 March 2016.

- ^ Minamikawa, S.; Watanabe, H.; Iwasaki, T. (2011). "Diving behavior of a faux killer whale, Pseudorca crassidens, in the Kuroshio–Oyashio transition region and the Kuroshio front region of the western N Pacific". Marine Mammal Science. 29 (1): 177–185. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2011.00532.10.

- ^ Chivers, S. J.; Baird, R. Due west.; McSweeney, D. J.; Webster, D. Fifty.; Hedrick, N. Chiliad.; Salinas, J. C. (2007). "Genetic variation and evidence for population structure in eastern North Pacific simulated killer whales (Pseudorca crassidens)" (PDF). Canadian Journal of Zoology. 85 (7): 783–794. doi:ten.1139/Z07-059.

- ^ a b Sergeant, D. Due east. (1982). "Mass strandings of toothed whales (Odontoceti) as a population phenomenon" (PDF). The Scientific Reports of the Whales Enquiry Institute. 34: 18.

- ^ Alonso, M. K.; Pedraza, S. North.; Schiavini, A. C. M.; Goodman, R. N. P.; Crespo, E. A. (1999). "Tum contents of false killer whales (Pseudorca crassidens) stranded on the coasts of the Strait of Magellan". Marine Mammal Science. 15 (iii): 712–724. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.1999.tb00838.ten.

- ^ "WDC". united states of america.whales.org . Retrieved 7 October 2018.

- ^ Hubbard, North. (x May 2016). "Drone films false killer whales hunting downwardly a shark". Earth Touch News Network . Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- ^ Palacios, D. M.; Mate, B. R. (1996). "Attack past false killer whales (Pseudorca crassidens) on sperm whales (Physeter macrocephalus) in the Galápagos Islands". Marine Mammal Science. 12 (iv): 582–587. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.1996.tb00070.ten.

- ^ a b c d Baird, R. W. (23 December 2009). "A review of false killer whales in Hawaiian waters: biological science, status, and risk factors" (PDF). Cascadia Enquiry Collective . Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- ^ Stacey, P. J.; Baird, R. W. (1991). "Status of the imitation killer whale, Pseudorca crassidens, in Canada". Canadian Field-Naturalist. 105 (2): 189–197.

- ^ Reeves, R. R.; Smith, B. D.; Crespo, E. A.; di Sciara, G. N. (2003). "Dolphins, Whales, and Porpoises: 2002-2010 Conservation Action Programme for the Globe's Cetaceans" (PDF). IUCN. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- ^ "Pseudorca crassidens –Fake killer whale". Australia Government Department of the Surround and Free energy. Retrieved three August 2018.

- ^ Eagland, N. (24 November 2017). "Merely ane cetacean remains in Vancouver Aquarium's tanks later a false killer whale died Friday morn". Vancouver Sunday . Retrieved 2 Baronial 2018.

- ^ "Imitation killer whale 'Chester' may accept died from bacterial infection: preliminary necropsy report". Global News. xxx Nov 2017. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ^ Brownell Jr., R. L.; Nowacek, D. P.; Ralls, K. (2008). "Hunting cetaceans with sound: a worldwide review" (PDF). Journal of Cetacean Research and Management. 10 (1): 81–88.

- ^ "Whale rescue in 1986 changed not just the people who were there". ABC. South West WA. 7 June 2011. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

- ^ "World watched as WA town saved the whales". The West Australian. 19 July 2011. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

- ^ "No further sightings of stranded whales". Department of Conservation and Land Management. 6 March 2005. Archived from the original on 7 September 2006. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- ^ Chambers, Due south. L.; James, R. Northward. (2005). "Sonar termination as a cause of mass cetacean strandings in Geographe Bay, due south-western Australia" (PDF). Proceedings of the Australian Acoustical Social club: 391–398. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 October 2006. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- ^ Kirkman, S.; Meyer, Yard. A.; Thornton, Grand. (2010). "Simulated killer whale Pseudorca crassidens mass stranding at Long Embankment on South Africa's Cape Peninsula, 2009". African Journal of Marine Science. 32 (i): 167–170. doi:ten.2989/1814232X.2010.481168. S2CID 84702502.

- ^ Staletovich, J. (xvi January 2017). "Mysterious stranding kills 81 false killer whales off Southwest Florida". Miami Herald . Retrieved 2 Baronial 2018.

- ^ "Accobams News". Archived from the original on 16 October 2021. Retrieved 20 October 2021.

- ^ Kearn, Rebekah (27 November 2012). "Hawaiian False Killer Whale Endangered". Courthouse News. Retrieved 27 November 2012.

External links [edit]

- Whale and Dolphin Conservation Club

- NOAA Fisheries Function of Protected Resources, Imitation Killer Whale (Pseudorca crassidens)

- Understanding on the Conservation of Small Cetaceans of the Baltic, North Eastward Atlantic, Irish gaelic and North Seas

- Agreement on the Conservation of Cetaceans in the Black Sea, Mediterranean Bounding main and Contiguous Atlantic Area

- Memorandum of Understanding Concerning the Conservation of the Manatee and Minor Cetaceans of Western Africa and Macaronesia

- Memorandum of Understanding for the Conservation of Cetaceans and Their Habitats in the Pacific Islands Region

- Voices in the Body of water - Sounds of the False Killer Whale Archived 9 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/False_killer_whale

0 Response to "to what order of animals does the sperm whale belong?"

إرسال تعليق